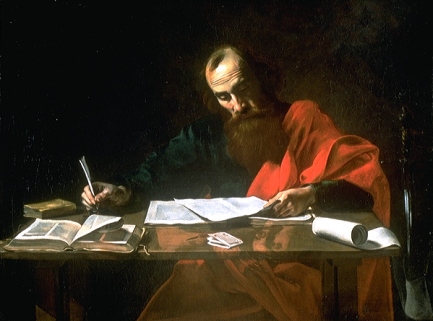

I’m entering the final stretch; all that remains are the Epistles and Revelations. An epistle takes the form of a letter. Many are written by Paul the Apostle, to this or that church in the time of his ministry. Others are written by other sources to a general audience. Romans is one of the former.

I’m entering the final stretch; all that remains are the Epistles and Revelations. An epistle takes the form of a letter. Many are written by Paul the Apostle, to this or that church in the time of his ministry. Others are written by other sources to a general audience. Romans is one of the former.

Epistles rest in a long-standing tradition. Scribes from Ancient Egypt, well into the Hellenistic and Roman periods would write such things to one another. An Epistle is a letter in form but serves a function of entertaining or more importantly, educating the reader. It is often moralizing, the literary equivalent of a passion play.

Good parts of the life of Paul were established in Acts. To recap; Paul was a Jew, born with Roman citizenship through his Father. He at first persecuted Christians, before falling from his horse and having a vision, which converted him to Christianity. He from there became an Apostle and went about spreading the good word to the Gentiles, establishing various churches.

For the sake of brevity, I won`t delve too deeply into the minutiae of determining when and where Romans was written. The middle of the 50`s CE is the most accepted date, and Cornith the most accepted place, but the scholarship gets pretty nitty-gritty pretty quickly.

At the time of this writing, Paul has been preaching for some time, establishing churches and what not. He intends to travel to Spain to establish more churches there, and thus, being in Greece will have an opportunity to visit Rome, as it’s on his way. The letter is thus to the Roman Churches in preparation for this eventual visit.

After opening pleasantries, Paul starts to put forward his theology. Parts of this will sound familiar by this stage; People have gone bad and that warrants some savage retribution from God. Sexual immorality and Idol worship draw particular attention, though so do a host of other sins. Paul centres Hypocrites as damned doubly by their actions.

Salvation theology is what follows; God is righteous and it is he that may cleanse people of sin. Believers are redeemed through their faith in Jesus Christ. Comparison is made between Adam and Jesus; As Adam, through his sin, condemned humans to die, so does Jesus, through his act of faith, restore life to the faithful.

He makes a theological argument that amounts to “Jesus died, and his death means Christians don`t have to obey the Masonic law”. This is useful of course, as it expands the potential realm of recruits beyond those who are willing to get circumcised and not eat pork, among other things. Or to be more academic about it; it enables a broader spread of Christianity that does not include adherence to traditions and mores that would be culturally alien in much of the Roman world.

Paul then laments for Israel and his fellows, feeling that their circumstances are a reflection of their abandonment of God(i.e. Jesus) and that if more followed his path, Israel would regain its status as God`s favoured nation.

There is more theology in this work than I have outlined, which makes it difficult to describe in succinct terms. It ends with a with an outline of Pauls`travel plans and a farewell.

This first of the Pauline Epistles is interesting in of itself as it has a different character from all the books we`ve read previously. While there have been varied forms in the content of the books; from a direct retelling of events to a discussion of law to a reading of prophecy, the Romans Epistles is a tad more intimate. It`was written by a man with the intent of being read by a particular audience, though perhaps not just that audience, though I imagine Paul might be a bit surprised to learn who would end up reading his work.

While the theology can be a bit opaque, and the style is obviously that of a 1rst century form transmitted over centuries and finally interpreted into English by 17th-century English translators, it does still offer us some peek at both Paul the man, and the state of the Church in this period.

The man who writes this believes in himself and his mission, and furthermore, writes to people he believes also believe in this mission. It has no air of supplication, but yet one of instruction, though neither is it particularly patronizing. It is a teacher and preacher in communication with others that are equal to him in terms of the community in which they operate, and yet whom he considers being potential vectors for his instruction. In some ways, it reminds me of communication between Scholars in the modern university system.

It would be hard for me to go over all the potential uses this particular work is put two, but a couple stand out; because this work references both the Jews as a group and in regards Masonic law, it comes up frequently in conflict with orthodox Jewish theology and in regards historical antisemitism. Beyond just the crucifixion of Jesus, the Jews are sometimes admonished with regards their abandonment of the path of God. This borrows obviously from the old testament, where Israel being punished for not following the true path is a recurrent motif.

This particular Epistle is also important as a source regarding the Protestant doctrine of ‘salvation through faith’. That is the belief that only Gods will and the faith of a believer result in salvation, not ‘doing good stuff while you’re alive’. Paul speaks of the importance of faith and the centre of divine faith and will in the Christian community.

As with many other religious traditions, we find here that directly the faith and the direction of the organizations of that religion are far much more than it’s sainted founder. As we will see by the number of Pauline Letters, and his place already in Acts, Paul plays a very central roll in Christianity.

Next, let’s feel some leather as we go to First Corinthians!